I spent my life sailing away from the shore, letting maps fade and compasses lose their north. You have to get lost to find yourself, they say. I haven’t found myself yet, but I keep looking.

I tore myself out of the city where I grew up. I transplanted myself to survive. The roots stayed behind, the fruit remained, everything still hurts. It sounds dramatic because it is. The city I grew up in is no longer the same. When I visit, its streets are smaller than they are in my love, dirtier, less colorful. Its drunks and drifters are no longer funny or familiar, the cars no longer part of a herd of domesticated relics. The block once full of kids chasing kites and baby-tooth balls watched them grow up and did not replace them. It chose to crack its asphalt, shutter its windows, and fall asleep under tufts of grass.

The first person to notice this was my friend Francisco, when he realized our fate was to stay boxed in or to change, and to this day he is the one who always goes farthest. Francisco left and felt sorry for me for staying. Don’t feel sorry for me, I remember saying, the pity I feel for myself is already enough. He came back a few times, searching for something. He always laughed, told stories, talked about how incredible the world out there was. But one Sunday night, just before leaving again, he cried and hugged me. He said that every time he came back, it felt like visiting the grave of someone dear. It was a cardboard city.

I only understood those tears when I was forced to leave too. I never thought of leaving that place, but it was that or die. I would have died, I’m sure of it. I was stabbed, the blood wouldn’t stop soaking my clothes and my floor. I didn’t want to end there, a resentful ghost.

I shoved a change of clothes into my backpack, the Kindle, a notebook, a ukulele (I still don’t know why I chose it), and bought a ticket to Warsaw.

I got off at the bus terminal and, while I waited and shivered with cold, I took out my notebook to jot down my impressions of that enormous place. I’d always heard that writers need to observe the landscape around them. Absorb nuances, sighs, smells, faces, see stories in details. They also say a writer needs to write about what he knows. But what I know is always very little. I wanted the moon, Tokyo, a medieval monastery.

As I scribbled my sentences, I realized there were only two possible approaches: research , immerse yourself as much as possible in the subject, read books, articles, watch documentaries, talk to people who know what they’re talking about, visit places, or pretend.

In my notebook, I pretended: Warsaw is woven from invisible threads of hope and despair, from which addicts and workers hang like puppets. Cars and motorcycles demand offerings of speed, time, and sometimes blood. In the midst of this frenetic ritual, I wondered whether I too was part of the spectacle or merely a distant spectator.

To pretend is to trust imagination. I will never set foot on the moon. So I pretend. I won’t go to Tokyo. So I pretend. I don’t know Warsaw, so I pretend. Imagination can fill the gaps and make you look at that part of the set where the budget money went, not at the Styrofoam furniture and the fake walls. But pretending the wrong way builds cardboard cities, like the ones Francisco feared.

I have lived and worked in Warsaw for a few years now. The knife wound throbs, especially when I walk alone along these narrow, uneven sidewalks. I wander lost, everything a labyrinth. My feet dance the off-beat waltz that only the city knows how to perform. These streets have their stories etched into cracks and corners, and they don’t always share them with strangers. I don’t share mine either. I swear I don’t understand. There, I feel here. Here, I feel there.

And then dusk arrives and paints everything with melancholy. A sun taking its leave, sliding slowly behind the cordillera of reinforced concrete. One by one, the streetlights and building lights begin to flicker on. They look like stars, if it were still possible to remember what stars look like in this very Polish sky. I think I love this place, but I hate it a little too. You have to get lost to find yourself. As I walk these unpredictable sidewalks, I ask myself whether my roots will one day find soil beneath the cement. If they don’t, I’ll pretend.

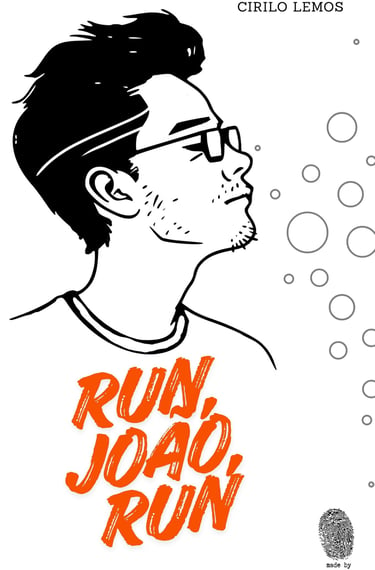

Cirilo Lemos

Warsaw

Masp (Divulgação/CASACOR)

Tolkien in Nova Iguaçu

Social media was on the verge of being invented in the head of some American college programmer. Isolated in Miguel Couto, Nova Iguaçu, I was the singular, the quintessential, a precursor of a new era in Brazilian literature, weaving a solitary cultural revolution, dragon by dragon, paladin by paladin.

I was preparing myself to become the master of Brazilian fantasy in the twenty-first century, a green-and-yellow Tolkien inventing fabulous worlds, devising complex geographies, populating lands with dwarves and elves, sprinkling in a Dark Lord here, a Chosen One there, a Final Battle somewhere else. A Cirilmarillion, haha (sorry about that).

I had no idea this was a larval stage of a generation of writers who wanted the same thing, a zeitgeist of pastiche, an atavistic explosion of cliché: emulating Tolkien, Rowling, Asimov, or (insert your favorite name here) trope by trope, tic by tic.

In my case, Tolkien.

Imitation is not mere copying. Imitation can be an interesting learning tool. By dissecting an engaging text, taking it apart and studying how each piece relates to the others, we can better understand what makes that author’s writing hook us like a big-bellied tilapia. This close analysis allows us to identify elements such as narrative structure, the use of metaphor, sentence rhythm, and the construction of characters and settings, which can then be absorbed into our own writing. Imitation becomes an exercise in conscious practice, in which we take in what works and discard what clashes with our own voice.

Playing with the box of tropes Tolkien handed down to Western fantasy proved useful in the construction of my own literary building. I realized, though, that I was not merely imitating. I was copying. Reproducing a Steven Seagal version of the Tolkienian legendarium. I changed a few things here, a few there, but everything was identical in intention (though obviously not in results).

I was even emulating the eternal revision of minutiae, which struck me as a fine excuse to feel like a writer without writing a single damn thing, like the theoretical magi of Susanna Clarke. I went so far as to decide I wouldn’t draft a single line of narrative until I had developed every last detail of the setting of my four-volume epic.

I began with the languages of the fantastical peoples. I got stuck there and stayed stuck. I had no talent whatsoever for linguistics, so I decided it would be more productive to come back to that later. Better to define the chronology of the world’s five ages first, some ten thousand years of History. I spent months describing lineages of kings and heroes, ancestral wars, cataclysmic events. I wrote bad poems about the creation of the universe, because that’s how the Ainulindalë began.

One day I was walking with a friend toward the neighborhood square. We were going to buy some junk to eat, maybe a hot dog (no mashed potatoes, please). There I was, describing my brave heroes to him while trying not to get run over by a motorcycle taxi, when I mentioned one of the main characters, a trickster elven illusionist.

“Always has to be an elven mage, right?” he said, casually.

I blinked a thousand times. What do you mean? Mine was unique. Sure, there were elves in lots of stories, fine, but mine was different because… because…

Because it just was, damn it.

That same friend later showed up with some cool drawings, loosely inspired by the illustrations of the old Tagmar. And he started talking about a setting he was developing for his RPG campaign, where there was the threat of the return of a Dark Lord and a Chosen One destined to destroy him.

How dare he? There was a Dark Lord in my story, there was a Chosen One in my story. There were in others too, fine, but mine was different because… because…

Because it just was, damn it.

Something hit me hard right there.

At home, I looked at the dozens of pages on which I had scrawled my epic, some handwritten, others typed on a cream-colored Olivetti I had borrowed from a cousin, and there was nothing there. No dialogue, not even the weakest kind, no character smiling, crying, living, no narrative, no showing or telling, nothing beyond notes about gods, cosmogonies, and invented words meant to simulate the languages of exotic peoples photocopied from The Silmarillion or the Player’s Handbook. But literature, none. Not a spark. Not a single miserable sentence.

That pile of notes interested no one but me.

I shoved everything into a cardboard box. I wanted that material far away (though not so far that it would keep me from going back to it, should I relapse). I was hurt and indignant. I stored the box on a shelf in my father’s workshop, a dark, dusty place like a dungeon in Angband.

Some time later, rain seeped in through a broken roof tile and turned the box into a lump of paper stuck together and stained with ink. I admit my chest tightened, like a Vala watching the Two Trees destroyed by Melkor and Ungoliant. But I think it was for the best. It was the equivalent of letting the One Ring fall into the lava of Mount Doom. I was free.

Don’t get me wrong: I still love Middle-earth, the Hyborian Age, Melniboné, Arton, Westeros, Earthsea. I still want to venture into my own maps someday. When—and if—that day comes, I won’t escape the influence of those authors, I know. But I’ll start from the premise that I can’t and don’t need to recreate The Lord of the Rings. I don’t need to tell in a four-book saga what I can tell in one. I don’t need to tell in a novel what fits in a novella.

Faced with the mass of paper and ink turned to pulp by the rain, the world lost one imitator of J.R.R. Tolkien. That was fine: there were still thousands out there.

As for me, I had moved on to the next stage in the journey of the aspiring Brazilian writer: imitating Rubem Fonseca, Clarice Lispector, Charles Bukowski, or Jonathan Franzen, Steven Seagal–style.

Cirilo Lemos

A collage featuring Tolkien with the city of Nova Iguaçu in the background. Historians believe the writer never set foot in Brazil.

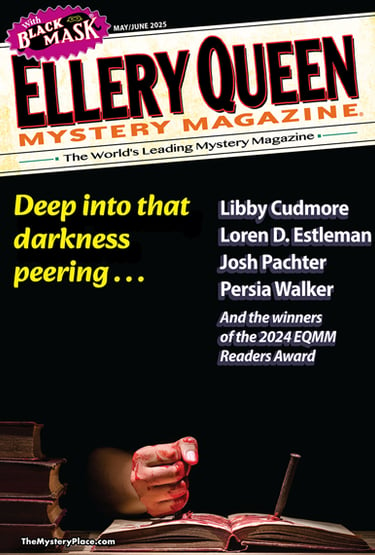

The Dead Detective's Affair

Ellery Queen Mistery Magazine May/June 2025

The Children I Gave You, Oxalaia

Clarkesworld Magazine Issue 216

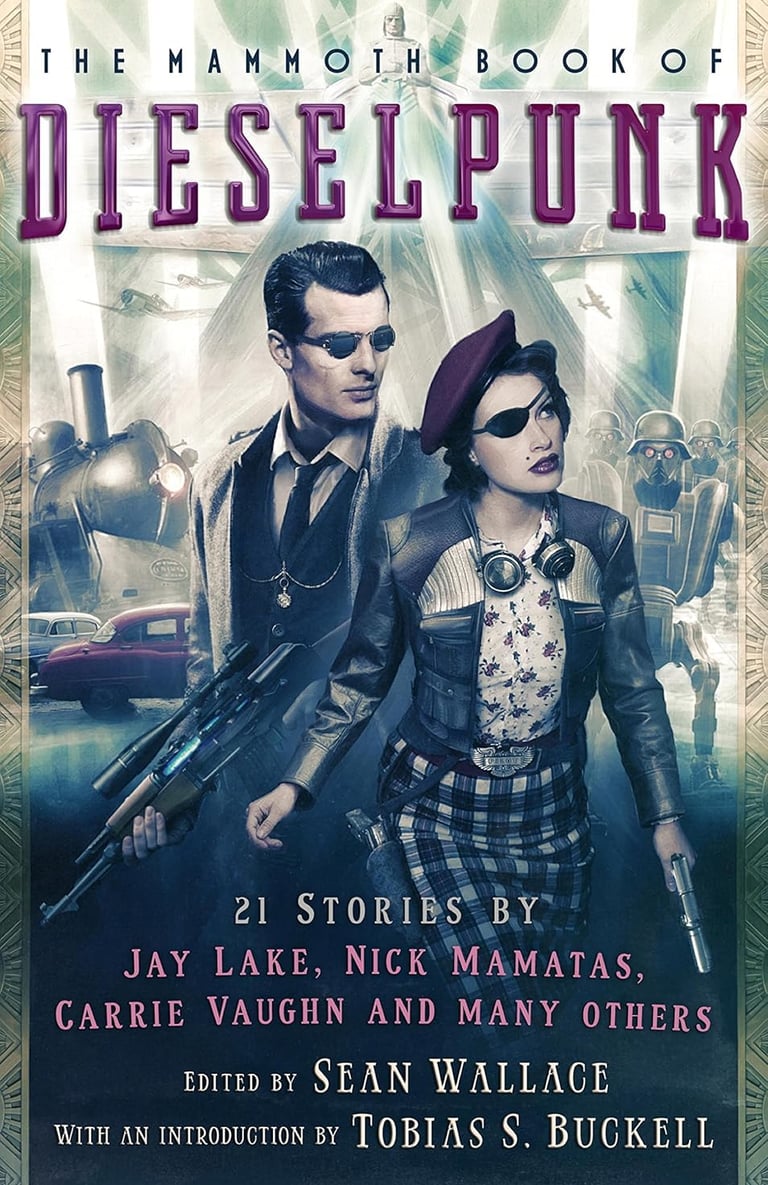

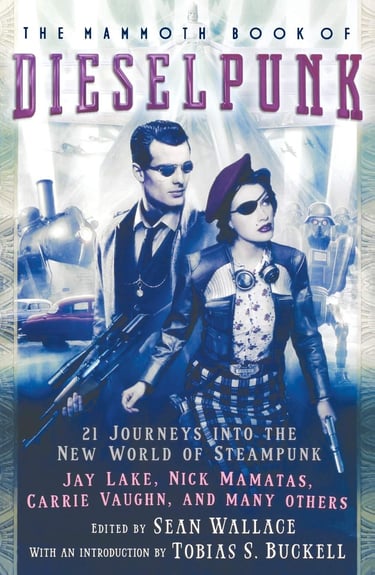

The Mammoth Book of Dieselpunk